This is a question I’ve been asking myself for a while. It’s not a fully-thought out argument (that’s why it’s still a question), but it’s a train of thought that I think warrants some investigation. I’d love to get some opinions from people with good or bad experiences of using DVCS with Agile as to how this plays out practically.

This is a question I’ve been asking myself for a while. It’s not a fully-thought out argument (that’s why it’s still a question), but it’s a train of thought that I think warrants some investigation. I’d love to get some opinions from people with good or bad experiences of using DVCS with Agile as to how this plays out practically.

So, here’s my train of thought…

Easy branching and merging is the killer feature of Git and Mercurial.

They improve on other centralised systems (Subversion, CVS) in many other ways, but branching and merging is the reason that’s always used to sell the switch. The question I want to raise is whether branching and merging are good tools for an agile development team, or a nuisance.

Branching is the Git Killer Feature Because Its Creators Needed It

Git was created by Linus Torvalds and the Linux kernel team. As a globally-distributed group of hundreds of volunteers working on any number of different enhancements at varying paces, the kernel team has a lot of work in progress, many teams working on orthogonal sub-projects within shared codebases, and a hierarchy of trust through which pull requests must be carefully ushered in order to be integrated. This is not the reality of most agile development teams.

Git was created by Linus Torvalds and the Linux kernel team. As a globally-distributed group of hundreds of volunteers working on any number of different enhancements at varying paces, the kernel team has a lot of work in progress, many teams working on orthogonal sub-projects within shared codebases, and a hierarchy of trust through which pull requests must be carefully ushered in order to be integrated. This is not the reality of most agile development teams.

Branches are inherently about creating isolation.

Why do you create a branch? Only for one of two reasons: to isolate those using existing branches from changes on the new branch (e.g. a feature branch), or to isolate the new branch from changes in its parent branch (e.g. a stable branch).

Feature Branches, in particular, avoid integration.

Integration is the process of taking your changes to the code, mixing it with other people’s changes to the code, and checking everything compiles, runs and passes tests so that you have a piece of potentially-releasable software. If you have a feature branch then you are intentionally not integrating; you are doing the opposite: isolating.

Side note: you can’t integrate by pulling without pushing.

I once raised with a DVCS evangelist the fact that having feature branches isolates you from other people’s changes. He told me that this wasn’t the case because his team (which was part of a larger project) was pulling from the main branch every day and hence integrating everyone else’s changes. He didn’t seem to realise that, seeing as every team on the project was using feature branches, there was little being merged into the main branch for them to pull, at least on a daily basis.

“Working software is the primary measure of progress.”

This principle is attached to the Agile Manifesto for a reason. In the good ol’ days, teams used to build separate components of their software in isolation, having agreed on how they would interface, then try to integrate them as a last step. Components would be “completed” according to the project plan, but there was no “working software”. You couldn’t say the component “worked” because it couldn’t actually do anything without it’s dependencies. Of course, once all this code developed in isolation was slapped together and tested, the usual outcome was, “Hey, look at that, it all worked seamlessly.” … said no one, ever.

This principle is attached to the Agile Manifesto for a reason. In the good ol’ days, teams used to build separate components of their software in isolation, having agreed on how they would interface, then try to integrate them as a last step. Components would be “completed” according to the project plan, but there was no “working software”. You couldn’t say the component “worked” because it couldn’t actually do anything without it’s dependencies. Of course, once all this code developed in isolation was slapped together and tested, the usual outcome was, “Hey, look at that, it all worked seamlessly.” … said no one, ever.

Continuous Integration prevents the pain of irregular integration.

Let’s be clear about what Continuous Integration is. It doesn’t mean running a CI server. It means checking valuable changes into the VCS mainline as often as possible. When Martin Fowler discusses continuous integration, he posits a general rule of developers checking into the mainline at least once a day, with a preference for more often.

It’s not unusual to see people who are still getting a handle on continuous integration fall into the trap of not checking in daily. I’ve noticed two common causes: either the task wasn’t broken down enough to be committable, or some change led down a rabbit hole and the pair didn’t realise until they were too deep. It can take as little as three or four days before developers will find that integrating their growing change set with the constant flow of small changes from the rest of the team turns into a moving-target nightmare. Such episodes will often be resolved through a request for the rest of the team to “please not commit anything for just a little while”. Developers who’ve been through this will usually realise straight away where they went wrong, share what they learnt with the team, and often become some of the biggest advocates of checking in frequently.

Continuous Integration is also a major form of communication.

In fact, Martin makes the claim that CI is primarily about communication. As developers, we are usually changing a small subset of a codebase at a time, but in order to make that change we’ll typically browse a much larger subset in order to orientate ourselves, check the details of things we depend on and ensure we’re following established patterns. While there’s often a relatively low chance that someone else on the team is changing the same files I’m changing, there’s a much higher chance (c.f. the birthday paradox) that someone on the team is changing something that someone else is relying on, but Git will never pick that up. And this is one of the really ugly and hidden dangers of delaying integration.

In fact, Martin makes the claim that CI is primarily about communication. As developers, we are usually changing a small subset of a codebase at a time, but in order to make that change we’ll typically browse a much larger subset in order to orientate ourselves, check the details of things we depend on and ensure we’re following established patterns. While there’s often a relatively low chance that someone else on the team is changing the same files I’m changing, there’s a much higher chance (c.f. the birthday paradox) that someone on the team is changing something that someone else is relying on, but Git will never pick that up. And this is one of the really ugly and hidden dangers of delaying integration.

No matter how good Git is at merging branches and conflicts in text files, it can never merge conflicts of understanding.

Continuous Integration mitigates the risk of undetected conflicts of understanding because it reduces the window in which such race conditions can occur to mere hours. Feature branches, on the other hand (along with traditional long-lived, uncommitted change sets), extend this window to last for as long as the branch is not integrated into the mainline. Remember, branches exist so we can have isolation, and that isolation shuts down the communication of changes in the source code.

Slicing by feature rather than component probably reduces integration risks.

The old-school method of slicing work by component meant that, for a piece of functionality to come together, the work of many different people had to be integrated. A core feature of the way agile teams work is that we develop stories – complete slices of valuable user function. When slicing this way, it’s not unusual to have the same people work across layers, sticking with the story rather than with a component. This often means the same people construct both sides of the integration, so they have the same knowledge, which reduces (though certainly doesn’t eliminate) the integration risks. Add in pair programming and frequent pair swapping and the risks may be reduced even further due to people actively sharing their knowledge with others from the team – others who may have related or even conflicting knowledge. (Reducing conflicts of understanding!)

So, you probably think I hate Git, but that’s not true.

I’m using Git. I think it’s a great tool with a lot more functionality than any of the various VCSs I’ve used before.

My concern is the effect the Git Koolaid has on agile teams.

Lots of people are migrating to DVCS because that’s where the action is. With a switch to Git or Mercurial comes a natural inquisitiveness about the best way to use branches – because that’s what these tools are all about – and everyone on the web is talking about their superior Git workflow. Agile teams that are serious about practising Continuous Integration of value need to seriously consider these questions:

- Should we use branches for day-to-day development at all?

- Do the benefits of practices like Feature Branching outweigh the costs of delayed integration and limiting communication?

Dave Farley (co-author of ‘Continuous Delivery’) describes Continuous Integration as the process of automatically creating a potential release candidate after every commit. Are feature branches going to help you do that?

Can DVCS, agile development and continuous integration fit together?

As I wrote at the start, I’ve been thinking about this for a while but it’s still just a train of thought, not some proof that it can’t work. Many others have written about this very same thing. Martin Fowler has written a superb, detailed description of how feature branches cause big conflicts and dealt with the proposed alternative of ‘Promiscuous Integration’. Derek Hammer, also at ThoughtWorks, has written about his team’s (failed) attempt to merge GitFlow and Continuous Delivery (pun intended!). Jade Rubick at New Relic has written about many disadvantages of long-running branches, Paul Gross at Braintree Payments has written a similar list of disadvantages with feature branching, and Jez Humble just says Feature Branches are evil.

As I wrote at the start, I’ve been thinking about this for a while but it’s still just a train of thought, not some proof that it can’t work. Many others have written about this very same thing. Martin Fowler has written a superb, detailed description of how feature branches cause big conflicts and dealt with the proposed alternative of ‘Promiscuous Integration’. Derek Hammer, also at ThoughtWorks, has written about his team’s (failed) attempt to merge GitFlow and Continuous Delivery (pun intended!). Jade Rubick at New Relic has written about many disadvantages of long-running branches, Paul Gross at Braintree Payments has written a similar list of disadvantages with feature branching, and Jez Humble just says Feature Branches are evil.

I’m yet to come across a blog that says “Feature Branching and Continuous Integration work really well together, and here’s how you do it…” If you’ve solved this conflict, I’d love to know how you’ve done it, and why. Please share in the comments.

Want to learn more?

Image credits:

‘Complicated‘ by Rohit Mattoo

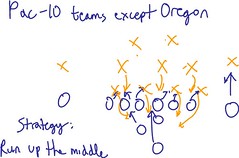

‘civilwarstrategy1‘ by Avinash Kunnath

‘Green Light‘ by Stephen Geyer

‘Broken Crescendo‘ by Francesco de Francesco

Gitg screenshot contributed by Mechanical snail on StackOverflow

The post Are Git and Mercurial Anti-Agile? appeared first on Evolvable Me.